Since its emergence in end the 2019, the deadly coronavirus (COVID-19) has been wreaking havoc on lives, livelihoods and economies across the globe. The character of viruses is to mutate and develop new forms and structures. COVID-19 is no exception and various mutations (at least 12 of these have been fairly widespread) of coronavirus have been identified since the first strain emerged in 2019. In late November this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified Omicron as a “variant of concern”. Not all mutations are a cause of worry. But Omicron, a variant of the COVID-19 virus which was identified in South Africa towards the end of November, has been identified as a variant of concern because it is known to spread much faster than other coronavirus strains. More alarming from a public health point of view is the concern that all the current vaccines are likely to be far less effective against Omicron as compared to other variants such as the Delta variant which caused the deadly second COVID wave earlier this year in India.

As scientists and public health experts tried to make sense of the ramifications of this new variant, and as governments across the globe rushed to shut down borders and restrict travel from South Africa and other countries in Africa, WHO’s Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus sought to highlight the inherent biases prevalent in public health policy in the world today. He spoke about lack of equity in access to vaccines, and how large unvaccinated populations lead to potentially more dangerous variants such as Omicron. Along with this, he shared a short video talking about the grossly unequal distribution of vaccines and the dangers of vaccine hoarding by rich countries. This video ended with a pithy tagline: “If the vaccine isn’t everywhere, the pandemic isn’t going anywhere”. The science is simple: if people in any part of the globe are not vaccinated in large numbers, this provides a fertile breeding ground for the virus to mutate and create new (and possibly more dangerous) variants of itself.

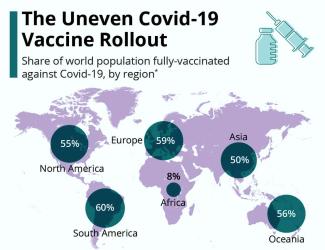

So we need to ask, if the science is so clear, then why have we seen such an abysmal vaccination track record in many parts of the world? An article in the British Medical Journal states that only 6.3 per cent of people in lower income countries have received one dose of the vaccine, and only 7 per cent of people in Africa (where Omicron was originally identified) are vaccinated (https://www.bmj.com/content/375/bmj.n3074). Only 1 in 4 of African healthcare workers have been vaccinated, compared to at least 75 per cent of healthcare workers in the global North. The contrast could not be more stark. While poorer countries are struggling to provide even one dose to even one-tenth of their populations, the US and UK are now giving booster shots to their citizens to protect them from newer and more dangerous variants, having vaccinated all those who wanted vaccines months back. This brings us to a crucial issue that we cannot and should not ignore: the issue of vaccine racism, and role of race and class structures and the role of the processes of colonialism, imperialism, liberalisation, privatisation and corporatization.

The Failure of the COVAX Model

When the COVID pandemic emerged, public health official were well aware that vaccine inequality would become a reality, unless collectively addressed by the world. As a result, COVAX was created – a global collaboration set up with the intention of ensuring that every person in the world would receive the vaccine. Poorer nations would be provided enough vaccines to vaccinate at least 20 per cent of their populations free of cost. This would be funded by rich nations and charities. Richer nations on the other hand would benefit from COVAX, because COVAX could provide them access to the best vaccines developed anywhere in the world. As a result of their collaboration with COVAX, rich nations could avoid entering into exclusive financial arrangements with each and every lab working on a possible vaccine. Instead, they could focus on some potential labs and hope to use vaccines developed elsewhere through COVAX. Like most other public policies, COVAX however failed because of the lack of political will and public sector financing.

Poor nations, who depended on COVAX for their vaccine supplies, were left high and dry; in the middle of the pandemic COVAX stopped communicating with them and as a result several countries had absolutely no idea when (if at all) they would be provided vaccines. These countries had then to look for alternatives sources of vaccines. Uruguay and Namibia for instance stopped waiting for vaccines from COVAX (vaccines that they had already paid for) and made their own deals with pharmaceutical companies, effectively paying twice. Countries who had the financial means to do so started making deals with vaccine manufacturers directly. But by this time, vaccine manufacturers had already committed their supplies to rich countries with whom they had contracts. Coming to the specific case of South Africa, when supplies from COVAX failed to come through, the African Union negotiated a new deal with Johnson & Johnson, and was promised 220 to 400 million vaccines. Most of this was never delivered and instead the company exported millions of vaccines to the US and EU. The figures are telling: 18 months after COVAX was formed, booster doses are being administered in the global north, while 98 per cent of people in low-income countries remain unvaccinated. Equally telling is the fact that COVAX has contributed less than 5 per cent of the all vaccines administered globally.

COVAX, when questioned about the failure to meet its mandate, has indicated that individual countries have scuttled their efforts. At the height of the second wave in India, India announced a de facto ban on vaccine exports from the country. Given the fact that India is a major vaccine manufacturer, this was a big blow to COVAX which required vaccines manufactured by the Serum Institute of India (SII). COVAX then asked wealthy nations to donate or sell excess vaccines which they had purchased and hoarded. One estimate states that the US and the EU together at one point had between 1 billion and 5 billion excess doses to redistribute. According to an article published by Stat, wealthy countries had pledged to donate 785 million doses to COVAX by the end of September 2021 and only 18 per cent finally arrived (https://www.statnews.com/2021/10/08/how-covax-failed-on-its-promise-to-vaccinate-the-world/). Moreover, even as COVAX was asking wealthy nations to share their supplies, it was also sending vaccines to them. As the Stat article points out, the UK, Canada and other rich countries have all received COVAX doses in 2021. In June, COVAX sent 530,000 doses to the UK alone. The entire continent of Africa received only four times that amount in the same period.

Deadly Role of Intellectual Property Rights

As COVAX failed, countries had to depend on individual contracts and agreements with vaccine manufacturers. This gave rise to yet another important concern. For more than a year, the UK and the EU blocked a proposal from South Africa and India and 100 other countries to suspend intellectual property rights (IPRs) related to vaccines on an emergency basis. Had IPRs for vaccines been suspended in the larger interest of public health, knowledge about vaccines could have been freely shared, vaccine production could have been localised and scaled up in many countries and vaccine shortages could have been handled much more efficiently. But thanks to the strong-arm tactics employed by the UK and the EU to veto such efforts, profits made by pharmaceutical companies were defended more than human lives in poor nations of the world. Companies, supported by powerful governments, held on to medical and technical knowledge about vaccine composition and manufacture. For example, when the WHO started building the first global manufacturing hub to produce mRNA vaccines with the cooperation of the South African government, Moderna and Pfizer refused to share any knowledge with the hub. In the absence of vaccines and any support from global vaccine manufacturers, African scientists have been trying to reverse-engineer the vaccines – a time-taking and unnecessary process, especially in the midst of a global health crisis. As a result of continuing protection of the IPR regime, large sections of the population in poorer nations remained unvaccinated. Infection and death rates remained high in these regions, and new variants emerged through large-scale spread of the virus.

Racism, South Africa and Omicron

The ugly face of racism has also shown up in this global panic around the coronavirus in general and Omicron in particular. Omicron has been detected in several countries including the UK, Belgium, Italy, Germany, Hong Kong, Israel, Australia and South Africa. South African scientists were however the first to identify the strain, and were subsequently singled out for travel bans. The US, for instance, did not ban travellers from all these countries, even as it banned people travelling from South Africa.

Secondly, Africa hosted a large part of vaccine trials, thus exposing its people to possible risks. And yet when the vaccines were finally approved, Africa received a very small share of the vaccines, as we saw earlier. Thirdly, even when vaccines began to be made available, South Africa’s healthcare infrastructure continued to reflect signs of its apartheid past, where access was deeply marked by racial boundaries.

Clearly, the experience with the pandemic tells us that it is equally a social, political and economic phenomenon. One cannot and should not study it as merely a medical and health disaster.