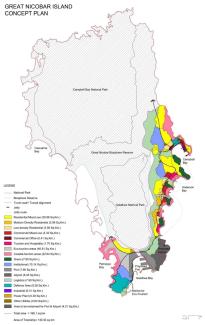

The Great Nicobar Island Development Project is a Rs. 72,000 crore mega infrastructure project envisioned by NITI Aayog in March 2021 claims to be part of ‘holistic development of Great Nicobar Island’. The project includes the construction of the following in the Great Nicobar Island (GNI):

- Galathea Bay International Container Transshipment Terminal (ICTT): A terminal with a capacity of 14.2 million TEUs (unit of cargo)

- Great Nicobar International Airport (GNIA): An airport with a peak hour capacity of 4,000 passengers

- Great Nicobar Gas and Solar Power Plant (Great Nicobar GSPP): A power plant with a capacity of 450-MVA spread over 16,610 hectares

- Two new greenfield coastal cities.

The 3 phase, 30 years long mega venture is to be executed by a government undertaking Andaman and Nicobar Islands Integrated Development Corporation’ (ANIIDCO). Two crucial approvals, the stage-1 in-principle forest clearance and environmental clearance have been already granted in late 2022. The Central Government is about to issue invitations for bids for the first phase of the terminal construction. The contentious mega project has raised several questions on prioritising profitable infrastructure over the need of preserving pristine biodiversity and upholding cultural and social rights of the indigenous communities.

An Unique Ecosystem

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands are divided by the 150 km wide Ten Degree Channel. Great Nicobar, a part of the Andaman and Nicobar archipelago, is the southernmost and largest of the Nicobar Islands, administered as a union territory in India. The island receives around 3,500 mm of annual rainfall and is characterised by the presence of lush tropical rainforest. The biodiversity rich island was declared a biosphere reserve in 1989 and in 2013 was included in UNESCO’s Man and Biosphere (MAB) Programme for its immense ecosystem services. The project site is located in Galathea Bay on the south-eastern coast of the Island.

GNI, a part of biodiversity hotspot with two national parks, a biosphere reserve, is inhabited by small populations of the indigenous communities, Shompen and Nicobarese tribal people, and a few thousand non-tribal settlers. The Shompen, around 250 in total, are classified as a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG) who mostly live in the interior forests having minimal contact with outsiders for centuries pursuing hunter-gatherer way of life. The coast dwelling community of Nicobarese having two groups: the Great Nicobarese (living along the island’s southeast and west coast and were forced to relocate to Campbell Bay from their ancestral lands after the 2004 tsunami) and the Little Nicobarese (mostly living in Afra Bay in Great Nicobar and also in two other islands in the archipelago, Pulomilo and Little Nicobar). Out of its total 910 km2 area, nearly 850 km2 is designated as a tribal reserve under the Andaman and Nicobar Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation, 1956. The region belongs to one of the most tectonically active zones.

Background of the Project

The idea of developing a port in GNI, near one of the world’s busiest international sea routes (the Malacca Strait) to boost participation in global maritime trade came into existence since 1970, when the Trade Development Authority of India (presently ‘India Trade Promotion Organisation’) conducted techno-economic feasibility studies. The current project labelled as ‘Holistic Development of Great Nicobar Island’ started after the NITI Aayog Pre-Feasibility Report (PFR) in August 2021, conducted by AECOM India Pvt. Ltd, a multinational consultancy firm. The International Container Transshipment Terminal (ICTT) targets to become a key player in the regional and global maritime economy by focusing on cargo transshipment. The proposed airport and greenfield cities are designed to support the growth of maritime services and international and national tourism activity.

Strategic location?

The PFR stressed on capitalising the strategic locational advantage of the island, which is approximately equidistant from Colombo (Sri Lanka) to the southwest and Port Klang (Malaysia) and Singapore to the southeast, to transform it into a global hub for ‘business, trade, and leisure’. The AECOM report says GNI “needs to trade on its remoteness and exquisite beauty. Some high net worth individuals will appreciate the chance to have a luxury home on such an unspoilt island”. It also states, that “if required tribals can be relocated to other parts of the island”. It adds, tourism development “can capitalise on the exceptional tourism assets to attract high-end tourists…”

GNI is situated just 90 km from the western tip of the Malacca Strait, a crucial waterway linking the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. It is also near the Sunda Strait, Lombok Strait, and the Coco Islands, making it vital for shipping, security, and maintaining a stronger military presence in the region to control key trade routes. It is to be noted that news reports have highlighted significant ongoing upgrades to the military infrastructure in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. The ‘strategic’ objectives of the project and the militarization of the island may heighten tensions between China and the QUAD as well as ASEAN countries potentially disrupting stability and forging arm competition.

On the other hand, the commercial aspect of the project questions its strategic dimension, as the AECOM report highlights an “economic development opportunity” tied to trade in shipping and tourism, suggesting commercial objectives are the primary driving forces behind the venture. To achieve the targets unhindered, it has been labelled as a "strategic project", making public disclosure easily avoidable, pointed out by many activists.

Role of regulatory bodies

There have been many objections and controversies regarding how the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Social Impact Assessment (SIA) have been done and clearances have been granted in a rushed manner. The role of the regulatory agency MoEF&CC has come under scrutiny as the details of the environmental clearance and appraisal process, which are typically public documents, have been kept confidential.

National Green Tribunal (NGT) and the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) facilitated the clearances instead of putting a check on such projects in this vulnerable ecosystem. The Directorate of Tribal Welfare of the Andaman and Nicobar Administration extended help in clearing regulatory processes, including for de-reservation of tribal reserve land for the project.

ANIIDCO, a little known quasi-government agency based in Port Blair is designated as the project proponent, responsible for coordinating and overseeing infrastructure development, land acquisition, relocation and concerns of the local communities. It is questionable how a company with Rs. 370 crore average annual turnover and Rs. 35 crore profit over the last three financial years, has been given responsibility for such a high profile project in an eco-sensitive region like GNI. When ANIIDCO was appointed as the project proponent in 2020, it did not even have any environment policy, environment cell, administrative system to ensure compliance with environmental clearance conditions or prescribed standard operating procedure or specialist to carry out the task. Still the Expert Appraisal Committee (EAC) granted environmental clearance to ANIIDCO in November 2022. It was only in late 2022 ANIIDCO started recruiting people with relevant technical, legal and financial expertise.

A petition filed in NGT by the Mumbai based Conservation Action Trust in 2022, elaborates multiple conflict of interests among the functionalities of regulatory bodies. When ANIIDCO was granted the forest clearance, its managing director was also the Commissioner cum Secretary (Environment and Forests) of the island, leading to a case of the project proponent certifying itself. Furthermore, the responsibility of assessing compliance with the Stage I forest clearance conditions lay with the same authority tasked with ensuring adherence to these conditions.

In April 2023, the Kolkata Bench of the NGT decided not to interfere with the environmental and forest clearances granted to the project. However, the project and its clearances have been under legal scrutiny at the NGT for alleged violation of the Forest Rights Act, 2006 and assessment protocols and formation of a high-powered committee was ordered to review the environmental and Coastal Regulation Zone clearances. An all-government high power committee, headed by the Secretary of the Environment Ministry, with members from NITI Aayog, ANIIDCO, MoEF&CC and its Expert Appraisal Committee who are directly associated with the project execution raises questions on its reliability and integrity. The Chief Secretary of the islands, who also chairs the board of directors of ANIIDCO, became a key member of this high powered committee as well. There is no clarity when and how the report has been submitted as it was made classified and not brought into public. The committee did not associate any independent institution or expert to ensure an impartial review.

Ecological implications

From the days of its inception, the mega GNI project has constantly faced criticism from environmentalists, wildlife biologists, anthropologists and tribal rights activists. The rainforests and beaches of the island acts as a huge carbon sink and is the home of numerous endangered species of flora and fauna including giant Leatherback turtles, the Great Nicobar Crake, Nicobar Megapode, the Nicobar crab-eating macaque, Nicobar tree shrew, hundreds of kilometres of mangroves and Pandan forests along its coast and other rare species of trees and corals. The proposed mega construction is going to adversely affect this rare ecological wealth by destroying coral reefs and the local marine ecosystem, and posing a threat on nesting habitats of terrestrial Nicobar Megapode bird and leatherback turtles.

The project requires the diversion of over 130 km2 of pristine tropical forest land, and has been granted a stage-1 clearance leading to the felling of around 1 million trees. In August 2023, the government informed the Parliament that 9.6 lakh trees could be cut down, with ‘compensatory afforestation’ planned thousands of kilometres away, in the vastly different ecological zone of Haryana. This kind of ecological compensation is not only farce but also raises concerns about its impact on the region's carbon sequestration capacity.

In order to expedite the project and pave way for the construction activities in otherwise prohibited areas, the Modi government, in January 2021 “denotified” two wildlife sanctuaries on the island including the Galathea Bay, one of the world’s largest nesting sites for the giant leatherback turtle and the Megapode wildlife sanctuary. The ‘National Marine Turtle Action Plan’ published by the central government during the same period enlists Galathea Bay as a marine turtle habitat in India. Both these species are listed in Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection Act), 1972 and categorised as highly protected animals. Leatherback turtles are considered as one of the oldest surviving creatures on the earth. There are a number of endemic species in GNI which are yet to be documented.

The proposed port is located in a seismically volatile zone that experienced permanent subsidence of about 15 ft following the 2004 tsunami. Despite this, the project proponents have not adequately assessed the earthquake risk. The Andaman and Nicobar archipelago lies within the “ring of fire”: a seismically active region that endures frequent earthquakes throughout the year. Estimates suggest the area has experienced nearly 500 quakes of varying magnitude over the past decade. The area is in category V: the geographical zone with the most seismic hazard making it highly vulnerable to natural disasters. The devastation caused by the 2004 earthquake and tsunami underscores the region's susceptibility to extreme weather events. Biodiversity loss, deforestation, change in land use, rising sea levels, inadequate disaster preventive and management plans and rapid commercial urbanisation is expected to exacerbate the island’s climate vulnerability. The extensive loss of carbon sinks due to land diversion, the lack of a clear plan for coral reef transplantation, and the potential loss of habitat for over 1,700 species of birds and animals are urgent issues that demand attention.

Violation of tribal rights

The project will be implemented over 30 years and is expected to bring more than three lakh people to the island by 2050 which is currently the total population of the entire Andaman and Nicobar Islands. As far as the GNI is concerned, the island will witness an increase of population at 4,000 per cent.

The GNI project is posing a massive threat to the survival of the Shompens and violates the sanctity of the Nicobarese peoples’ ancestral lands. Shompen and Nicobarese are dependent on the resources of the riparian and forested parts of this proposed project area. The Shompen are categorised as a vulnerable tribal group having special needs and rights and their population is reported to be just 250. The project will gradually lead to social displacement of their indigenous settlements violating their rights and needs for land, water, resources, culture etc. The arrival of people from outside could expose these tribes to diseases against which they haven’t yet developed immunity. Moreover, the proposal to use geofencing (barbed wires) for the ‘protection and safety’ of Shompens, due to the power plant being situated close to their habitat, is both brutal and regressive and appears to be a tactic to confine them to their own land. In February 2024, experts from around the world urged President Draupadi Murmu to abandon the project, warning that it could lead to the extinction of the Shompens.

The ancestral lands of the Nicobarese and some Shompen settlements have been wrongly classified as “uninhabited” in the NITI Aayog’s plan. Since 2004, the Nicobarese have repeatedly sought to go back to their ancestral (pre-tsunami) lands but the current relocation plans in the mega project do not address this long standing demand. The government is exploiting the displacement of the native Nicobarese caused by the 2004 tsunami to facilitate a massive land grab under the guise of 'development' agenda.

The island administration appears to be rushing forward with the project, disregarding the rights of local tribes by manipulating consent. The National Commission for Scheduled Tribes, a constitutional body, has sought an explanation from the district administration on this matter. It is important to note that the Forest Rights Act mandates free, prior and informed consent from tribal and other forest-dwelling communities before any relocation can take place, meaning relocation is not a predetermined outcome. When assessments are conducted using selectively ascertained justifications, the resulting reports are likely to reflect bias. In this case, the local administration failed to adequately consult the Tribal Council of Great and Little Nicobar Islands, as required by law. In November 2022, the tribal council revoked the no-objection certificate it had previously issued for diversion of about 160 km2 of forest land, citing that the administration had misled them and withheld critical information regarding the use of tribal reserve lands.

A group of experts have written to the National Commission of Scheduled Tribes (NCST) highlighting how the clearances granted to the project are fraught with legal inconsistencies and how it will be harmful for the region’s indigenous population. More than half of the GNI project lies over the Tribal Reserve Area, but officials claim that no tribal reserve is part of the proposed project. This is because 84.10 km2 of tribal reserve area has already been denotified, effectively stripping the area of its protected status to accommodate the project. In their letter, they stated that such diversion of tribal land violates constitutional mandates. To compensate for the reduction of the Tribal Reserve and safeguard the habitat of the Shompen and Nicobar tribes, the Andaman and Nicobar Administration proposes to re-notify 76.96 km2 of land within Campbell Bay National Park, Galathea National Park, and areas outside these parks as Tribal Reserve. But this pragmatic move is extremely dangerous as it is based on the flawed assumption that any land can be considered equivalent and therefore replaceable to meet the needs of the tribals. This approach reflects the UT administration's lack of understanding and insensitivity towards the unique requirements of indigenous communities and the bio-geophysical diversity of the island.

The local panchayat of Campbell Bay also raised concerns over the SIA process for land acquisition for the airport due to lack of transparency and accountability. The SIA including the Public hearing was conducted ignoring the traditional inhabitants of the region, Shompen and Great Nicobarese, thus violating the A&N Islands Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation (ANIPATR). The hearing held on June 29, 2024, to address the concerns of the ‘project affected community’ invited residents of Gandhi Nagar and Shastri Nagar, two Gram Panchayats of Campbell Bay, where settlers from mainland India were relocated between 1968 and 1975. Notably, the 117-page long draft SIA, fails to assess the impact of the mega infrastructure project on the interests of the original inhabitants and does not mention these two communities even once defying the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013. A group of 103 former civil servants raised serious objections to the SIA report in a letter addressed to the secretaries of the Ministries of Tribal Welfare and Home Affairs, the Social Welfare Department of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and Chairman of the National Commission for Scheduled Tribes, terming the report as ‘superficial’.

Conclusion

The GNI project needs to be seen in the light of massive deforestation drives in Hasdeo, Buxwaha, Dehing Patkai as a part of Modi governments pro corporate profit seeking policies aiming ‘ease of doing business’.

Despite tall claims about economic growth and geopolitical strength of this project, its potential to cause an ecocide has made several environmental activists, academics and anthropologists to write to the government highlighting its unconstitutional nature and harmful environmental and social impacts urging for its withdrawal. The process of ‘transforming’ an extremely fragile eco-sensitive zone into a hub of trade, tourism, and strategic military presence, is embarked with the hallmarks of ecological, seismic and humanitarian disaster and has been rightly coined as a perfect example of ‘disaster capitalism’ by activists. The project prioritises a singular model of economic development through large-scale infrastructure, where progress is envisioned at the expense of indigenous peoples' rights and the destruction of a unique ecology. This venture deliberately undermines the pro-people and pro-environment sustainable policies and is driven by economic and strategic interest favouring larger corporations and investors over local lives and livelihoods.