This important article first appeared in The Leaflet, April 4, 2022. The authors are Arvind Narrain, author and legal scholar; and Clifton D’Rozario, who practices law to protect the rights of workers and oppressed peoples, and is Karnataka Secretary of the CPIML Liberation. The article analyses three insightful books on the persecution of Jewish lawyers in Nazi Germany demonstrates that even in the most difficult circumstances, it is possible to keep making a difference to people’s lives; that the spirit of resistance can be nurtured even when it is impossible to exercise the right to speech, assembly and association; and that an oppressed advocate can still be the advocate against oppression.

The fate of the Jews in Nazi Germany is relatively well known, but till the publication of German political scientist Simone Ladwig-Winters’ book ‘Lawyers without rights: The Fate of Jewish Lawyers in Berlin after 1933’ by the German Bar Association, there was little attention paid to the fate of Jewish lawyers as a grouping.

‘Lawyers without rights’ is an extraordinarily moving documentation of what happened to Jewish lawyers in Nazi Germany. Jewish lawyers comprised a significant section of the Bar in Weimar Germany; the Nazi capture of power led to them being progressively restricted from practicing the law and eventually eliminated from the legal profession.

The fate of Jewish lawyers in Nazi Germany is important to understand from two aspects. Firstly, from the viewpoint of the method used by the Nazis to target Jewish lawyers, which combined both violence on the street as well as the use of the law. Secondly, to understand the important role that lawyers can play in any legal system. The reason for targeting Jewish lawyers is because lawyers could exist independent of the State and, wittingly or unwittingly, strengthen the voice of resistance to the policies of the Nazi State. Lawyers, if allowed to function unhindered, would have, through their practice, been an impediment to the unconstrained lawlessness of the Nazi rule.

The fate of Jewish lawyers in Nazi Germany illustrates this progressive radicalization of the State and society, as it imposed more and more controls based on a blatantly racist viewpoint.

We often think of the end point of Nazi rule being the Holocaust, but fail to see that the Holocaust itself became thinkable and doable because of a range of steps which led up to it. The fate of Jewish lawyers in Nazi Germany illustrates this progressive radicalization of the State and society, as it imposed more and more controls based on a blatantly racist viewpoint.

Strangulating the right to practice law

Ladwig-Winters documents how this ban came about, beginning with what he calls the “[t]he first wave of exclusion: terroristic attacks against Jewish attorneys”. Four weeks after Adolf Hitler comes to power in 1933, a fire set to the German Parliament is instrumentalised by the regime to pass an emergency decree which suspended “key basic civil rights: personal freedom, freedom of speech, of the press, of association and assembly…” This dramatic increase in power of the State results in the arrest of more than 5,000 political opponents, especially Communists, Social Democrats and other opponents of the Nazis.

Also arrested are Jewish lawyers including Alfred Apfel (released after 11 days), Ludwig Barbasch (released after six months), and Hans Litten, who remained in prison till his suicide. Also arrested is a “rather inconspicuous attorney Fritz Ball”, who records his experience of arrest, torture and finally his release in a haunting report found in the publication of his brother, writer, lawyer and Israeli historian Kurt Jacob Ball Kaduri. Ball records his experience at the improvised concentration camp this:

“I am immediately surrounded by a dozen of quite young SA [Sturmabteilung, which was the Nazi Party’s paramilitary wing] people. I am interrogated as to what my name is, where I live, what political party I belong to and how I voted in the elections…. ‘Are you a Jew?’- ‘Yes.’ – ‘Your profession?’- ‘Attorney at the Berlin Court of Appeals and Notary.’ ‘That’s something you have been for a long time,’ someone screams out behind me in front of the crowd. ‘Tomorrow you Jewish pigs will all be driven out of the courts. You have our Fuhrer to thank that you are still alive today.’”

Ladwig-Winters recounts the arrests of other lawyers during this time since they were “first and foremost opponents of National Socialists” and “above all, the fact that they were also Jews was given emphasis in the propaganda relating thereto”.

Post the emergency decree, the SA marched into courts in many cities in Germany, assaulted Jewish lawyers and forced them to leave the court premises. Ladwig-Winters calls this “[t]he second wave of exclusion” where Hitler and his party took recourse to a dual strategy – they increased the “terror from below”, in order to push through their political interests “from above”. With staged spontaneous acts, which included open violence, seemingly unavoidable circumstances were created that required the State to undertake political policies that were appropriate “for the maintenance of public law and order”.

“Instead of arresting lawyers in the dead of night, they attacked courthouses in the light of day. SA men – the so-called brown shirts, uniformed thugs – stormed courthouses and occupied them, searched for Jews and chased them away. Invariably, police arrived on the scene too late.” In American legal historian and criminal defence attorney Douglas G. Morris’ book ‘Legal Sabotage: Ernst Fraenkel in Hitler’s Germany’, a lawyer who witnessed this shocking scene gives us a sense of how the world of law and justice was turned upside down:

“There were judges, prosecutors, and lawyers, many in their official robes, who were driven onto the street by small hordes of SA men. Everywhere the intruders flung open courtroom doors and bellowed, ‘Jews out’.”

The vigilante action was followed by Nazi decrees which disbarred Jewish lawyers and judges from the profession (subject to some exceptions, such as those having served in the First World War on the frontlines). The decree, in turn, was supplemented by continuing pressure by the SA on ordinary people to boycott Jewish lawyers. This decree was followed by another which barred Jews from being appointed as notaries or judges, and downgraded Jewish lawyers to consultants without the right to represent in Court but only to give advice, that too only to Jewish clients. Those who were still practicing law saw their earnings dwindle to a fraction of what it was, with many of them forced to close their offices and work from home. Ladwig-Winters called this the third wave of exclusion which also saw targeted segregation, and transfer of Jewish judges and prosecuting attorneys. The consequence was that “[o]n the one hand, the appropriate stacking of the court with judges impeded the criminalization of National Socialists who committed acts of violence; on the other hand, the judicial examination of exclusionary measures in individual cases was prevented.” Finally, in the last wave, the Nazis passed a decree in September of 1938 which simply outlawed all Jews from practicing law.

The Nazi war against Jewish lawyers began with ad hoc and brutal actions of murder and mayhem against lawyers, which sent shock waves through the community. This was followed by the passing of rules, regulations and decrees which were used to lawfully deprive Jewish lawyers of the very right to practice law. The Nazi strategy of elimination of Jewish lawyers from the legal profession “combined Nazi law and lawlessness.”

Memorialising the victims

‘Lawyers without rights’ tells us the stories of courageous lawyers who fought against the system, as well as lawyers who were victimised by the system for being Jewish, even if they had no other strong political convictions. What Ladwig-Winters does is to give a sense of dignity to all those who had their lives as Jewish lawyers upended by the Nazi State. Towards that end, the book documents the lives of a total of 1,404 attorneys of Jewish origin, with some of them ending up in concentration camps, others killed, and yet others opting for emigration as the only way forward.

In giving dignity to those whose humanity was so cruelly trampled upon, Ladwig-Winters also tells us the story of some extraordinary defiance by lawyers against the regime.

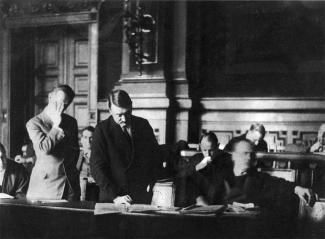

One of the narratives of courage is that of Hans Litten who was “known for his defence of communist workers who had been involved in fights with National Socialists”. Litten was a lawyer with strong political convictions and at the young age of twenty eight, he achieved fame as the lawyer who fearlessly summoned Hitler as a witness in a case in which the Nazis were being prosecuted for their acts of violence. His “clever questioning strategy”, made Hitler “extremely miserable”. This resulted in a “deep hostility of Hitler against him”, and immediately after the Reichstag Fire, he was arrested and taken to several concentration camps and brutally tortured. Litten, after five years in concentration camps, hanged himself when he was thirty-five. His funeral was a “small affair, attended only by his mother and one of her friends.” At his funeral, his mother insisted that the organist play a passage from German composer and musician J.S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion that she had recently discussed with her son – a passage that she doubtless thought resonated with his isolation and death, the passage after Jesus Christ was taken prisoner before his crucifixion and the Evangelist declared, ‘Then all his disciples forsook him and fled.”

Ladwig-Winters also resurrects the life of attorney and notary Ludwig Bendix, who lost his licence to practice law after the second wave of Nazi measures adopted after April 1933. He was then arrested in June 1933 for his defence of a member of the Communist Party. Released later in October the same year, it was made clear to him “that he was being taught a lesson”.

Bendix informs his clients that he has been compelled to give up his practice. He continues to operate as a legal consultant advising those who seek to leave the country. He refuses to escape the Nazis because Germany was his home and he would seem like a traitor if he abandoned his country:

“Despite all the disappointment and intimidation, I am not going to let myself be beaten down… It may seem crazy, but I insist on another viewpoint. I fight for every inch of ground and cling to it with every fibre of my being… My undying struggle to regain the life that has been taken from me has created an inner necessity that drives me forward, despite all differentiations and discrimination, to affirm a shared heritage with those who now hold sway over the country and people and to leave it to personal disputes with them to draw a line in individual instances. I regard it as my duty to myself to maintain my personal dignity by making use if every possibility offered by the laws currently in place…”

Bendix is again arrested in 1935 and imprisoned till 1937 in the Dachau concentration camp, and released under the condition that he would immigrate to a country outside of Europe. He went to Palestine.

Bendix’s commitment to “making use if every possibility offered by the laws currently in place”, provides a fitting epitaph to all lawyers who bravely and till the very end resisted the regime, making use of their training as lawyers.

Lawyering within Nazi Germany

The one detailed narrative we have of lawyering in Nazi Germany is that of German-Jewish lawyer and political scientist Ernst Fraenkel, who theorized his experience of lawyering in Nazi Germany in ‘The Dual State: A Contribution to the Theory of Dictatorship’. Fraenkel is also the subject of ‘Legal Sabotage’, an extraordinary jurisprudential and biographical account of his work in Nazi Germany by D.G. Morris.

Fraenkel, who had a thriving labour law practice representing labour unions, saw that practice collapse when the Nazis simply outlawed labour unions. While his partner, political activist, Marxist theorist and lawyer Franz Neumann was forced to flee Nazi Germany as he was prohibited from practicing law, Fraenkel continued to practise law in Nazi Germany due to the exception for those who had served on the frontlines in World War I, as he had.

Speaking of his motivation to stay in Germany when the writing on the wall was quite clear as far as Jews were concerned, Fraenkel had said that “some [of us] had to remain in Germany whose presence and silence could provide those who could not leave some feelings of assurance and of not being abandoned.” Fraenkel’s work over five years in Nazi Germany is a testament to being that ‘presence’ as a lawyer, political activist and theorist.

As the Nazis progressively tightened the noose around Jewish lawyers, his practice moved from labour law to defending those accused of crimes by the Gestapo (the official secret police of Nazi Germany). His career in Nazi Germany as a practicing lawyer from 1933 to 1938 raises an important question: what are “the possibilities of liberal lawyering in a dictatorship?” His career is an illustration of the different strategies by which one man sought to resist the dictatorship under extremely difficult circumstances.

To understand the difficulties of lawyering in a dictatorship, it makes sense to compare it with the possibilities in a democracy, however imperfect. In Weimar Germany, an essential aspect of human rights lawyering or political lawyering was an appeal to the court of public opinion. “Publicity had energized Weimar defence lawyers”, who used “political trials to promote their agendas and attack their adversaries.” In Nazi Germany, “publicity vanished from the arsenal of leftist political lawyers”, with the press being intimidated into silence.

With the press disappearing as an option for amplifying the voice of human rights lawyers, what was left was the “remnants of legal procedure which were still operational in the courts.”

The one method still available to opponents was legal procedure. One profession that, in the words of the German international relations scholar Jens Meierhenrich, “withstood the destruction of democracy in the 1930s” and persisted as “one of the remnants” of the Rechtsstaat (the German variant of the rule of law) was lawyers. Thus, Fraenkel and other lawyers could still “represent political defendants in court and mount a defence by minimizing or even denying their clients’ acts.”

However, as Fraenkel was to go on to analyse, the legal procedure which the courts followed had to be contextualized within the emergence of what he was to call the ‘dual [S]tate’. By this, he meant that Nazi Germany was an uneasy coexistence of two States, the ‘normative [S]tate’ that generally respects its own laws, and the ‘prerogative [S]tate’ that violates the very same laws. For Fraenkel, “…the essence of the prerogative [S]tate is its refusal to accept legal restraint, i.e. any ‘formal’ bonds.”

The prerogative State was embodied in the Gestapo, which had the power to arrest a person without any legal authorisation and detain a person without providing any information as to where the person was. In effect, if a person landed up in the custody of the Gestapo or what Fraenkel was to call the prerogative State, there was no recourse available with the person disappearing into a legal black hole.

In one case, Fraenkel’s client was arrested on charges of insulting the Fuhrer because he had been overheard by an overzealous SA man muttering “that is all old cheese” on seeing the latest issue of the Nazi weekly Der Sturmer. Fraenkel’s client told him that he had not been referring to the Fuhrer but rather to the photo which had appeared in an earlier issue of the paper. Fraenkel dug up the earlier paper and found that what his client told him was true. In a State bound by rule of law, the evidence which Fraenkel had would have clinched the matter and his client would have been acquitted. But Fraenkel knew that if his client was released, he ran the risk of being picked up by the Gestapo and disappearing into a legal blackhole. So in spite of presenting his evidence to argue for an acquittal, he was concerned that an acquittal would be increasing “the risk of a new arrest”. Therefore, Fraenkel’s strategy was to skip “any factual defence” and limit himself to “discussing the appropriate sentence”. His client was finally convicted but served a relatively brief sentence. Most importantly, his client evaded the Gestapo.

Going beyond law: Pamphleteering in Nazi Germany

While as a lawyer, Fraenkel worked within the limitations of the Dual State, he was also an activist. As an activist, he defied the law by writing articles critical of the Nazi State. If his authorship of the anti-Nazi articles was discovered, he ran the risk of arrest and detention in concentration camps. He wrote an early article called ‘The Point of Illegal Work’, in which he argued that illegal work must be ‘visible work”, visible to the Gestapo and the police. The point of visible ‘illegal work’ was to restore the morale of individual Social Democrats, especially after “socialism’s ignominious collapse in 1933”, and create the moral authority needed for “a rebirth, or better put, a new birth” of German socialism’s political power.

In a later pamphlet which Morris infers is also written by Fraenkel, he writes:

“Yes, we have become ‘criminals.’…If we were not empowered by our illegal activity, I fear that we too would sink into the smog that oppresses Germany. Because we work illegally, we keep ourselves fresh…That is the point of illegal socialist work in the Third Reich: to infuse the workers with strength, the waverers with trust, the sufferers with hope and the rulers with fear. Does illegal work have a point? What would Germany be without illegal work?”

In another piece titled ‘Revolution in Criminal law’, he lambasted the Nazi amendments to the criminal law. Morris, in his summary of Fraenkel’s piece, notes:

In its worst transgression, the 1935 amendment extinguished the principle that judges could punish perpetrators only for acts that were explicitly prohibited – that is to say, for crimes that statutes defined. Rather, the law permitted prosecutions for acts that statutes failed to cover but that nonetheless deserved punishment because of ‘healthy popular feeling.’ The time-honoured principle of liberal law, ‘no punishment without law’ (which German jurists often refer to in the Latin phrase nulla poena sine lege), gave way to a new Nazi principle, which Fraenkel dubbed ‘no crime without a punishment’.”

However, Fraenkel does not end on a note of pessimism, concluding his article on the 1935 amendment stating that it “provides…a new valuable piece of evidence in the educational work of showing more and more people that the Third Reich is not a state but a robber’s den.”

The illegal work of writing pamphlets and ensuring that they were distributed was never straightforward in Nazi Germany. ‘The Point of Illegal Work’ had to be smuggled out of Germany to Holland, printed there, and then smuggled back to Germany. “The article – resting in desk drawers, carried by people who had to steady their pulsating anxiety, rolling through machines that rapidly pressed ink, read in quiet rooms scattered throughout Nazi Berlin – took a journey that was unusual for a piece of scholarship.”

Illegal work was a vital supplement to legal work and allowed Fraenkel to express his real feelings about the regime.

Theorising the Nazi State

However, as the Nazi regime entrenched itself by late 1936, the “possibilities for opposing the Nazi regime in court” began to disappear and “the dangers of subverting it in secret” began to mount. According to Morris, Fraenkel himself had lost the rhetorical passion that had fired his earlier essay, ‘The Point of Illegal Work’, and he was shifting from “hoping for the resistance to losing hope.” However, “what he never lost…was his drive to understand”.

He turns from writing articles to researching and writing about the nature of the regime that he is confronting, which he famously characterizes as the Dual State. The importance of the work flows from the fact that it was written from within the heart of Nazi Germany, relying explicitly on publicly available court documents and judgments, and implicitly on the author’s experience of being a lawyer in Nazi Germany.

Fraenkel’s motivation in writing the book was the hope that he could contribute “to a scientific discussion (that is, a scholarly evaluation) among all those who are convinced that one of the means to overcome dictatorship is the analysis of its true character.”

The ‘Dual State’ was an important theorisation emerging from someone who lived through Nazi persecution and was attempting to make sense of the regime. The fact that the State encompassed the normative State and the prerogative State also structured Fraenkel’s activism, with his attempt being at all points in time to ensure that the victims of Nazism remained within the jurisdiction of the normative State as opposed to the prerogative State.

In Fraenkel’s understanding, even the Nazi regime could not totally eliminate the normative State. The commitment of a normative State to predictability and consistency enabled by law was absolutely essential for ‘monopoly capitalism’. For Fraenkel, the “prerogative [S]tate allowed the normative [S]tate to function to the extent that it advanced monopoly capitalism.” There is a striking contrast between the position taken by Fraenkel who “attributed more importance to the role played by law” than his former law partner Neumann. Neumann went on to write his book analyzing Nazi rule called ‘Behemoth: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism, 1933-1944’ when in exile. For Neumann, unlike for Fraenkel, law under the Nazi regime was “nothing but a technique or transforming the political will into legal form”.

In ‘Dual State’, Fraenkel searches for a principle which could ground anti-Nazi resistance. For him, the question was to “find legal authority outside the state justifying a German resistance”.

Fraenkel is a committed socialist whose opposition to the regime comes from his socialist convictions. However, as Nazi repression intensified, he realised that the targets of the Nazis included socialists, communists as well as Christians. In particular, he was moved by the unwavering opposition of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who embody an “uncompromising opposition to military service” and were willing to defy the Nazi state to worship their God. He saw that “no other group opposed the regime so fundamentally”, and wondered what the inspiration for their resistance was.

The answer, according to him, lay both in their belief in the “western tradition of rational natural law” as well as their belief in the importance of conscience. Nazism was fundamentally opposed to the idea of a natural law, which derived its authority from a rational understanding of the nature of human beings. “Rational natural law was beyond nation, while Nazism promoted the interests of a single nation, race, or community. Rational natural law assumed the equality of people, while Nazism assumed their inequality. Rational natural law set forth abstract norms that governed conduct, while Nazism reduced all conduct to expediency, in particular to racist nationalist expediency.”

Fraenkel then posits an allegiance to ‘rational natural law’ as a way of grounding opposition to the Nazi regime. He realizes that the anti-Nazi opposition is small and shrinking. As he puts it, “there were never many and there were with time fewer and fewer”. For him, an allegiance to ‘rational natural law’ could be a way to “attract as many anti-Nazi opponents as possible, extending beyond the proletariat into the bourgeoisie”. He then turned his attention to developing his thesis of “the united front of the promoters of rational natural law.”

Quite obviously, while ‘rational natural law’ lacks the power of more emotive ideologies, the question remains: what could have been the ideological basis for mobilizing resistance to Nazism within Nazi Germany? Fraenkel essays one answer, which tries to find a common ground between the Christian groups and socialists when it comes to resistance.

Fraenkel is himself working in a particularly difficult context. Over a short period of time, all collective resistance to the Nazi project had been smashed. All that was left were resisters who were “loners” as a “matter of temperament”. Loners did not “need the approval of others” and “drew energy from self- motivation”. In times of dictatorship, loners were critical because the hall mark of such resistance was ‘decentralisation’, and hence more difficult to detect and eliminate. When all collective forms of resistance are eliminated, what is left is the human conscience, which continues to keep alive the tradition of resistance.

Contemporary relevance

What does it mean for us in contemporary India to read both ‘Lawyers without rights’, which is a tribute to Jewish lawyers during the holocaust, as well as ‘Legal Sabotage’, which is the story of one Jewish lawyer, Ernst Fraenkel, and how he resisted the Nazi State during the period from 1933 to 1938 before he was driven into exile ?

U.S. Supreme Court judge, Stephen Breyer, makes a powerful case for why ‘Lawyers without rights’ is invaluable. In the foreword to the book, he says that it is “important that we and future generations remember the misuse of laws in Germany and how it permitted a society to effectively purge a significant group of lawyers solely because of their religion, sending many in exile or to their deaths. It is about the misuse of law”.

Reading ‘Lawyers without rights’ is also about asking how did this happen, and why did “non-Jewish lawyers in Berlin and Germany…step aside and offer little resistance to the dismantling of their profession as well as to the substitution of jurisprudence in Germany with Hitler’s law.”

Finally and most importantly, a book about the past is also about the future. As the President of the Berlin Bar Association put it, “The response to this book in the past years is an encouraging sign of hope that there never again will be attorneys without rights in this country”. By reading this book, we should be alert to what is going on in our own country. Are there straws in the wind which indicate that the hard won independence of advocates is under threat?

Going from the large picture of advocates under threat in ‘Lawyers without rights’ to the micro picture of how one such extraordinary advocate, Fraenkel, negotiated the Nazi dictatorship in ‘Legal Sabotage’ is instructive. Even under the most difficult conditions, there were people who carried on resisting the Nazi regime. Moving between what was possible in legal practice to authoring pamphlets criticizing Nazi rule to finally writing a book about the nature of the Nazi State, Fraenkel kept alive a tradition of resistance within Nazi Germany. Morris’s account of Fraenkel’s work under difficult circumstance is about telling the story of how those “who believed in the rule of law, legal equality, and social justice” could “play the cards that life had dealt them to oppose tyranny”.

For Morris, “the career of Ernst Fraenkel in Nazi Germany poses a dilemma. How did he accomplish as much as he did – as a covert pamphleteer, an overt political lawyer, and a scholar – and still avoid arrest? The resolution of this dilemma poses another question. What might Fraenkel’s accomplishments under the Nazi regime show about the possibilities of liberal lawyering in a dictatorship?”

Fraenkel’s extraordinary career, brought out by Morris, tells us that even in the most difficult circumstances, it is possible to keep making a difference to people’s lives, and that the spirit of resistance can be nurtured even when it is impossible to exercise the right to speech, assembly and association. Ladwig-Winters, in restoring dignity back to the Jewish lawyers through the act of remembrance, opens to us the brave lives of Hans Litten, Fritz Ball and Ludwig Bendix, and the possibility of the oppressed advocate still being the advocate against oppression. These narratives help us cultivate possibilities of courageous action even in dark times.

Image: Lawyer Hans Litten cross examined Hitler for 3 hours during the 1931 trial against Hitler's SA Rollkommando that had attacked the Eden Dance Palace, popular with left wing workers, killing 3 people and injuring many others.