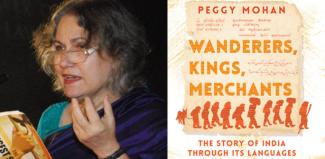

Wanderers, Kings, Merchants: The Story of India Through Its Languages,

by Peggy Mohan, published Penguin Books, April 2021

Is it possible to write the history of a nation through its languages? This is what distinguished linguist Peggy Mohan does, in a very lively way in her book Wanderers, Kings, Merchants: The Story of India Through Its Languages.

This book questions the idea of purity of the race/language/culture. Human history is a history of constant travels, mixings, wars, empires, slavery, and resistance and so on. When cultures and languages face each other it is not always a harmonious interaction. In this process some languages lose their identity and continue to live in the other language through words, idioms or sounds. Mohan draws a powerful image of the process- "When a hardy local tree is lopped off and a more delicate exotic variety is spliced on the stump, there is often a graft line- a mark that remains even after the final tree is grown. Our journey in this book is to uncover the signs in India that reveal this moment of fusion..."[pg. 26].

Why are these graft marks important? They are important because they remind us of our hybridity and negate the supremacist ideology. The dominant narrative tries to hide these graft marks to create a monolithic sense of history to carry forward the agenda of Hindu supremacists. The idea of one culture, one language, and one religion is handy in creating the 'other' while the idea of the hybrid character of culture makes it difficult. In recent times some popular books have come out to challenge this idea of purity and oneness. Tony Joseph’s book Early Indians: The Story of Our Ancestors and Where We Came From and this book of Peggy Mohan's should be read together. Another

Mohan starts her story by narrating the process of formation of creoles in the Caribbean and its origin with the rise of slavery. It is interesting to know that creoles were created not by first generation slaves but by their kids and the coming generations.

As a teacher of Hindi language and literature I got to know the genesis of some problems faced during all these years while teaching Hindi sounds to non-Hindi speaking students. Students especially from north-eastern states find it difficult to pronounce T, Th, Da, Dha, Na (tukade, thakur, damru, dhaal etc.). Mohan takes us on the journey where we see the emergence of these retroflex sounds in some languages and discomfort with these sounds of some other languages. Mohan’s book also challenges many of our own long-held ideas about language and culture. We used to believe that Sanskrit is the language of Aryan “oppressors”, and that North Indian languages are derived from Sanskrit, as opposed to Dravidian languages of South India, especially Tamil. Mohan complicates this story, by establishing that it is Dravidian languages that have shaped the entire sound system of Sanskrit: a sound system permeated by the dental versus retroflex sounds. And she traces this impact back to the relationships between Aryan male immigrants and local Dravidian women; where the former held on tight to the words of their own central Asian language but nested those words in the grammatical structure of the local women’s language. Likewise, local languages, spoken by the women to their children, survived as Prakrits, using many loan words from the dominant Sanskrit but spoken in the local accent. She also notes how “avoidance of voiced aspirates” (the ‘h’ sound in words like bhat) is a feature found in the languages of the North-west as well as South India. This, she suggests, is because “modern Punjabi, Sindhi, Balochi and Pashto have what looks like a Dravidian substratum.” This radically challenges our ideas about the relationship between the languages of North and South India.

Origin of Hindi and Urdu, their nativity and cultural universe has been a very contested and emotive issue among even best and well-meaning academics. Mohan has dealt with this question from a linguist's point of view and raises some fresh questions and suggests some new lines of enquiry. She has established that retroflex sounds is the DNA of south Asian languages and that Vedic Sanskrit adopted these sounds. She draws a parallel with the coming of the Persian and Arabic to India with the coming of Vedic Sanskrit. Then raises a question why these languages did not adopt retroflex sounds. She suggests that if Aryans would have arrived with a written language rather than an oral one, the course of history might not have been the same.

This book is a must read for those who are interested in the history of language but do not have a taste for the erudite linguist's technical language. The style of writing is informal and witty. Sometimes you can break in to laugh while reading it. In a chapter she is writing about her meeting with historian Irfan Habib at AMU and tells how their discussion got derailed. When Professor Habib got her point "He paused and scrolled back a full millennium..." These kind of expressions make this book a good read.