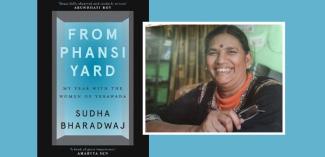

[A Review of Sudha Bharadwaj’s book 'From Phansi Yard: My Year with the Women of Yerawada' (Juggernaut Publication, 2023)]

‘So Madam, what exactly is your case?’, asked the bewildered police constable sitting cozily in the room of the person who was under house arrest. After all it’s very unusual that the person you and your colleagues from the local thana are watching over accommodates you in her spare bed room. One begins to wonder how such an amicable person could be hounded by the law! But then Sudha Bharadwaj is no ordinary person. The very fact that the respected social worker, trade-union karyakarta, human rights activist, people’s lawyer is most comfortable when she is among the people, made her a suspect in the eyes of the law. It was only natural that this kind of a person would realize from the very beginning of her imprisonment that it was only by watching, learning and trying to understand the numerous women around her that she would be able to cope with her incarceration.

She was a high-security prisoner, locked up in the Phansi Yard of the impregnable Yerawada jail in Pune almost for the entire day with barely any opportunity to interact with the other prisoners. But that didn’t deter her. She found out ingenious ways to talk to and learn about the other women, be it in the lock-up, mulakat room, or in the van on the way to the court. In this way she documented the lives of seventy-six women, the many heartbreaks, betrayals they faced, their many loves that turned sour, the dear ones who at some point deserted them. Her portraits of these women were by no means complete, for she only had the opportunity to view some fragments of their lives. Whatever she came to know she jotted down meticulously and gradually the book ‘From Phansi Yard’ took shape.

What she saw in the prison didn’t as such shock her. Having been a lawyer to the downtrodden of Chhattisgarh she was already aware of the various prejudices that plagued the judicial system. She was also aware of the pitiable conditions under which people lived in the jails of states like Odisha and Chattisgarh. But viewing a system from the outside and becoming a part of it is entirely different. When she herself was incarcerated, she began to realize the sheer enormity and the depth of the problem. Various aspects of the prisoners’ lives simply astounded her. She began to understand first-hand the crippling effect of patriarchy on the inmates’ lives, the temporary relief that religion and festivals brought, the distorted ways in which laws are implemented.

If one were to choose one single aspect that most shocked her, it was the all-encompassing effect of patriarchy on the lives of these women. International Women’s Day is celebrated with much fanfare in the jail. But there is no discussion on patriarchy or the many struggles women have waged to strive for equality and dignity. There are only cultural activities, mostly of the very crass type. The rehearsals and the actual performance provide some relief for the prisoners. But sometimes the message rendered by these activities is deplorable. For instance the message of a play seems to be saying, ‘all that we suffer is because of the sins of our past lives. And if you are a woman, you must have been a very oppressive man in an earlier life.’

She relates incident after incident in which women martyr themselves to save the men in the family. So many women are willing to sacrifice themselves for their husbands, sons, boy-friends or brothers. There is the instance of an elderly bageechewali (who works in the garden for a pittance) whose daughter-in-law died in a fire. The author writes that maybe she was a nagging, harassing mother-in-law but the fact is she and her son were not at home when the incident happened. And even the Bahu didn’t name her Saas in her dying declaration but the son, to save himself, blamed his mother for the crime. He was acquitted but her mother is rotting in prison! She narrates another incident of a woman who had an affair with a married man. When the wife was murdered, she, the husband and his two friends were arrested. These three men conspired to put the entire blame for the murder on the woman. When she was informed about it she was nonchalant and repeatedly murmured, ‘but I love him!’ Reflecting on the impacts of patriarchy, the author also describes the Maratha girl who so endearingly describes her relationship with a Tamil boy and the way they had eloped and married. The author couldn’t believe it when she came to know that the same bubbly young woman had abetted the rape of the ex-girlfriend of her brother for having cheated him of a few lakhs of rupees. How could such a free-spirited woman abet the rape of another, she wondered.

Being free of the clutches of men, women can openly air their opinions in prison. They speak out against the oppression at home. It is revealing when someone exclaims: ‘We are very blessed here. Just think – not having to work, only washing one’s own clothes and vessels. No husband to order us around. No mother-in-law to nag us if we nap in the afternoon. No stream of guests to feed and serve endless cups of tea to….’ Family life is so patriarchal that even prison is preferable for many women!

Fights are a way of life in jail. Fights occur every day on the flimsiest of issues. The prisoners are rarely at fault though. The jail is overcrowded; its capacity is 129 but the total number of inmates fluctuates between 250 to 300. So there is a shortage of facilities, and lines for everything --- ‘to piss, to shit, to get food, to cut your nails….’ It’s a wonder that more terrible incidents do not occur every day. In this context one remembers Justice Madan Lokur’s comments after the death of Father Stan Swamy. He had said that conditions in Indian jails are abominable due to three factors. Jails are overpopulated, almost bursting at the seams; the surroundings are very unhygienic and filthy, and thirdly the paucity of toilets leads to choking and utter uncleanliness. Significantly he had said that these conditions amounted to ‘soft torture’ of the prisoners.

On the other hand there is friendship as well, but any intimacy is risky when it develops into solidarity. You cannot stand up for your friend. The moment one does that, there is every possibility that she will be banished to a different barrack. A large number of women are implicated in cases of violence. If one delves a bit deeper then one will find that the woman herself had been a victim of domestic violence for years. She had been so tortured day in and day out that after a certain period her patience snaps and she strikes back. Our judicial system doesn’t take into account this persistent violence she has suffered but punishes her for her retaliation. Indian criminal law also has other serious loopholes which the author highlights. Firstly it is often found that entire families are picked up on the death of a daughter-in-law. In one instance a girl who had been married into the family for only fifteen days was also incarcerated. How could such a new entrant in the family be a part of the conspiracy, the author wonders. Secondly, while the law was amended to counter domestic violence, it is often found that the women of the ‘offender’ family are also jailed though there is scant evidence against them. Thirdly, patriarchy is so embedded in the system that there is absolute apathy and indifference to the numerous complaints of beatings and torture. Only when there is a death of the daughter-in-law, or of someone else due to her retaliation, does the system begin to stir.

The author says that the only culture allowed in jail is religion. Indeed jail life is more syncretic than outside life. There is hardly any distinction made between the three main religions. The logic is, what’s the harm in worshipping a god if he helps me in getting released. As a result many non-Muslims observe roja, many non-vegetarians look forward eagerly to the chicken meal during Id. Christianity is also very popular. During Christmas inmates are allowed to purchase cakes baked in the bakery. Christian organizations often come to hold prayers and sing carols. Inmates look forward to their visits because these organizations distribute warm clothing, cakes and soaps for the children. Diwali and Ganesh Chaturthi are also celebrated with much fanfare. One is allowed to purchase laddoos and other sweets during these festivals. Except religion no other collective activity is allowed in the jail. Any kind of togetherness or efforts at organization is swiftly scuttled. Looking back the author wonders if we have regressed as a nation. During the British period stalwarts like Gandhi, Nehru, Lokmanya Tilak were imprisoned here. They held political meetings inside the jail premises but now in independent India one cannot even think of it. What’s more now political ‘crime’ is considered more heinous than general crime. Political cases are dealt with most sternness but all types of privileges may be allowed to the regular prisoners.

Being a lawyer, one of Sudha Bharadwaj’s most frustrating experiences was to find many women not being able to get release even after getting bail. Either they are unable to pay or unable to provide sureties. Usually it is difficult to get a surety, who has to be from the same district and possess property. Most inmates are poor and in many cases their families have deserted them. They work in the jail but the wages they get are very low. With that meager amount they are unable to procure bail, leave alone starting a new life after release. But the author’s greatest disappointment was to find that many women hardly get proper legal help. Their families cannot afford the fees to engage proper lawyers. So in such cases legal counsel is provided by the Legal Services Authority. But the author finds that such lawyers are not accountable to the prisoner. The lawyer doesn’t know anything about her case, even her next court date, the charges against her etc. These lawyers, themselves poorly paid, do not consider it their duty to keep the prisoner informed.

Reading the above account it would be wrong to conclude that a prisoner with UAPA hanging over her head passes a comfortable time in jail documenting the lives and experiences of her co-prisoners. We have no idea about the ordeal of passing long hours in an isolated single cell. Inevitably one becomes overly anxious. All the health problems seem to become more amplified. Patches on the plaster of the stone walls evolve into many shapes and become eerie faces or animals. Sleep eludes her and late into the night she writes. A favourite kitten snuggles up to sleep next to her. Perhaps then the author remembers the searching question by that lady constable, ‘so madam, what exactly is your case?’ Having spent almost a year in prison she isn’t too sure of the answer still now. In fact she isn’t much worried about that. When she was transferred to Byculla jail, on someone’s request she sang some lines composed by Sahir Ludhianvi, the poet: ‘Voh subah kabhi toh aayegi.’ She is convinced that some day that morning will dawn. When she came to the lines, ‘Jailon ke bina is duniya ki , sarkar chalayi jayegi’, not a single prisoner’s eyes around her were dry.