While Sri Lanka’s present is certainly messy and chaotic and the future may be uncertain, it is instructive to take note of how Sri Lanka landed in this crisis. Much of India’s media and social media commentary about Sri Lanka seeks to blame the Rajapaksa family and its ‘dynasty politics’ for the present disaster. The anger of the Sri Lankan people too is primarily directed at the Rajapaksa family. True, no dynasty has been as powerful and as nepotistic and plunderous as the Rajapaksas. Initially, when Mahinda was President, Gotabaya was his Defence Secretary when the two brothers waged a vicious war to crush the LTTE. Their youngest brother Basil was the minister in charge of economic development while the eldest brother Chamal was Speaker. It is said that as many as forty Rajapaksas held one office or another and controlled the entire Sri Lankan economy. Mahinda lost the Presidential poll in 2015, but Gotabaya became the President in 2019 and appointed Mahinda his Prime Minister.

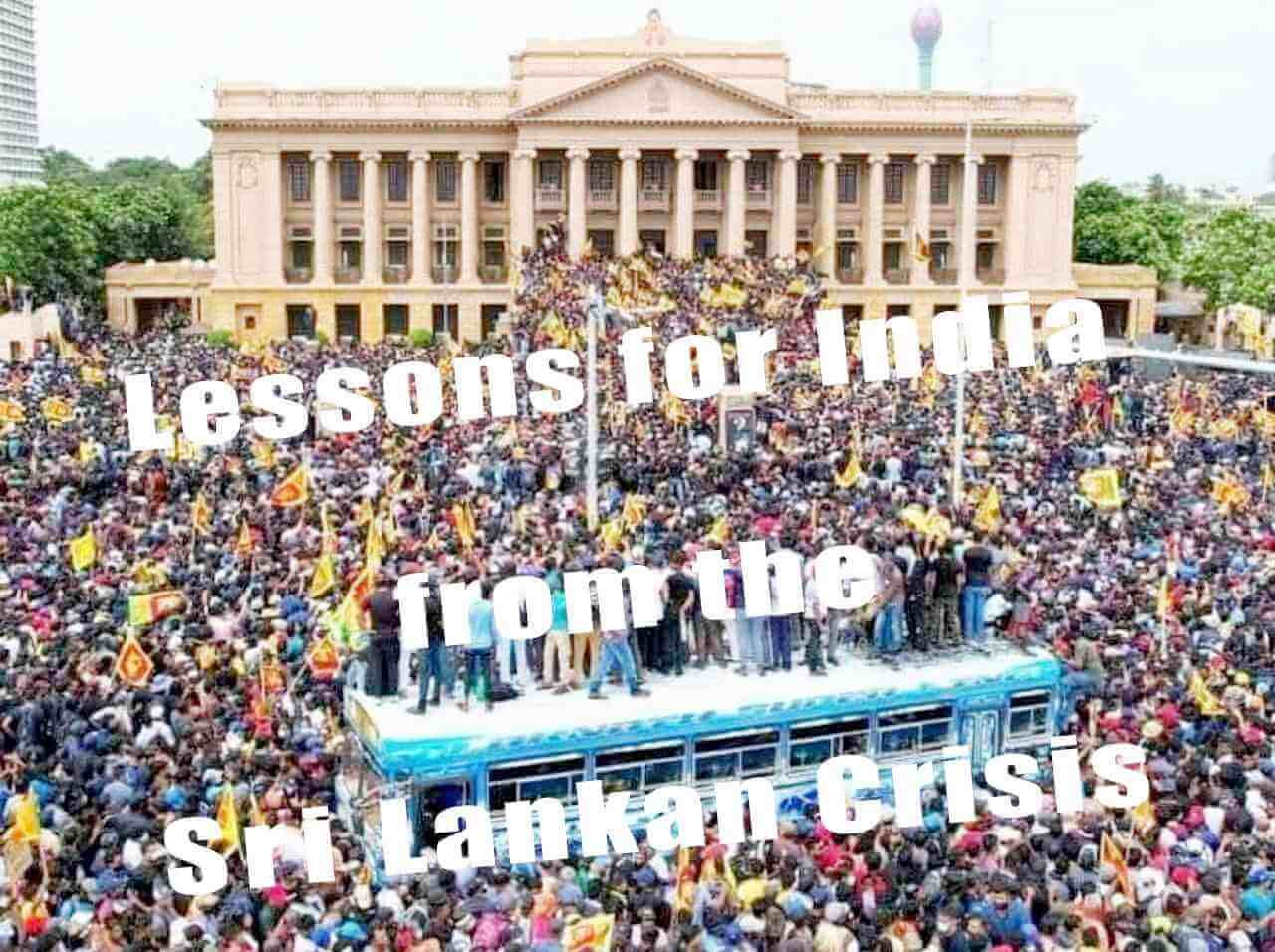

With absolute power came absolute corruption and absolute mismanagement and arbitrary governance. In the name of spurring growth, in end 2019 the Rajapaksa government gave sweeping tax concessions to the rich and also slashed Value Added Tax from 15 percent to 8 percent and abolished several taxes. The number of tax paying citizens dwindled from nearly one and a half million in early 2020 to less than half a million in 2021. Meanwhile the pandemic affected Sri Lanka’s income from tourism and remittances and the foreign exchange reserves dropped from 8.8 billion dollars to less than 2.5 billion. Even as the pandemic eased a little, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine badly affected the supply chain of essential imports. Soon Sri Lanka was reeling under soaring prices and acute shortage of food, fuel and medicines. As protests began, Gotabaya declared a public emergency on April 2 and within three months Sri Lanka is facing this unprecedented upsurge of the people.

The question to ask is how did the Rajapaksas manage to become so powerful and get away with their misrule for so long. This is where we need to look at Sri Lanka’s political situation. After crushing the LTTE through a brutal military crackdown, the Rajapaksas projected themselves as the saviour of Sri Lanka. Mahinda Rajapaksa became a mythical hero, a demi-god. To consolidate the grip of the government, the regime gave a free hand to the newly launched militant Sinhala Buddhist outfit Bodu Bala Sena. With the LTTE decimated, Sri Lankan Muslims became the next target for aggressive Sinhala Buddhist nationalism. The discourse and trajectory of events in Sri Lanka in the last couple of decades resembles the Indian trajectory almost like a mirror image. Mahinda Rajapaksa’s attempt to concentrate more power in his hands following the amendment of the constitution to remove the two-term bar on presidency did ring some alarm bells and he suffered a shock defeat in the 2015 elections. But the 2019 Easter bombings just ahead of the Presidential elections brought the Rajapaksas back amidst the clamour for a strong government. Since the two-term bar had already been restored by the Opposition, Mahinda could not contest the Presidential poll and brother Gotabaya, who had been playing a predominantly military role till then, sacrificed his American citizenship to become the President.

The acute economic crisis and mismanagement has turned this super strong Sri Lankan government riding on a wave of aggressive Sinhala Buddhist chauvinism into a clueless entity that Sri Lanka cannot afford any more. The backdrop of this eruption of public anger lay in the brazen nepotism, authoritarian governance and utter economic mismanagement, the hallmarks of the Rajapaksa regime which did not however seem to matter as long as the crisis was not acute enough to stir the people out of the intoxicating stupor of the Buddhist-supremacist Sinhala nationalism.

This is precisely where India should learn from Sri Lanka. On a strictly economic comparison, India probably has a bigger cushion in terms of forex reserves and fundamental economic strength. But Indian economy too has been subjected to similar kind of mismanagement and arbitrary measures in the Modi years beginning with the debilitating demonetisation and half-baked GST to the continuing subversion of the public sector and transfer of public assets to a few chosen private hands. Prices have been going through the roof, unemployment is at an all-time high and the value of rupee in the international currency market is at its lowest. And yet, there is hardly any discussion on the economy and the living conditions of the common people; the entire focus is on promoting communal polarisation and eroding the institutional framework of Indian democracy. Let us not forget that just two years ago Sri Lanka’s Human Development Index was 71 out of 189 countries while India languished at 131. Sri Lanka tells us that the combination of communal polarisation, corporate plunder and tyrannical governance is a definite time bomb waiting to explode unless measures are taken on time to change course.